Insights

We are proud to be named a West Coast Regional Leader for 2025

From worthless to worthwhile: Maximizing insolvent CFC value

ARTICLE | January 14, 2025

Authored by RSM US LLP

Executive summary

Navigating the labyrinth of worthless stock and bad debt deductions can be particularly challenging when applied to financially distressed controlled foreign corporations (“CFCs”). This article provides a high-level overview of the relevant U.S. federal tax law, particularly in the international context. It explores the mechanics and implications of claiming worthless stock deductions under section 165(g) and bad debt deductions under section 166 as they relate to CFCs. Additionally, the article examines the treatment of Subpart F income and the impact of the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (“GILTI”) regime introduced by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (“TCJA”), highlighting the multifaceted nature of these tax rules and their significant implications for U.S. shareholders of financially distressed CFCs.

Introduction

Navigating the labyrinth of worthless stock and bad debt deductions can be particularly challenging when applied to financially distressed controlled foreign corporations (“CFCs”). This article provides a high-level overview of the relevant U.S. federal tax law, particularly in the international context. It explores the mechanics and implications of claiming worthless stock deductions under section 165(g) and bad debt deductions under section 166 as they relate to CFCs. Additionally, the article examines the treatment of Subpart F income and the impact of the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (“GILTI”) regime introduced by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (“TCJA”), highlighting the multifaceted nature of these tax rules and their significant implications for U.S. shareholders of financially distressed CFCs.

Controlled foreign corporations

Generally

A controlled foreign corporation (CFC) is defined under section 957[1] as any foreign corporation in which more than 50% of the total combined voting power of all classes of stock entitled to vote, or more than 50% of the total value of the stock, is owned by U.S. shareholders on any day during the taxable year of the foreign corporation.

U.S. shareholders of a CFC are generally required to file Form 5471, Information Return of U.S. Persons with Respect to Certain Foreign Corporations. This form mandates the reporting of detailed information about the CFC, including its financial statements, ownership structure, and transactions between the CFC and its U.S. shareholders. Additionally, it requires the disclosure of CFC items that may be reflected as income for the U.S. shareholder.

Subpart F income

The Subpart F rules, introduced in 1962, prevent U.S. shareholders from deferring tax on certain types of "movable" income, such as dividends, interest, rents and royalties, by earning income through CFCs in low-tax jurisdictions. Under these rules, U.S. shareholders must include their pro rata share of the CFC's earnings in their current-year income, regardless of whether the income is actually distributed. This inclusion increases[2] the shareholder's basis in the CFC stock, which is then reduced[3] when the previously taxed income is distributed, preventing double taxation.

GILTI

GILTI is one of the largest post-TCJA anti-abuse principles to prevent offshoring of profits to low tax jurisdictions.

GILTI requires U.S. shareholders owning at least 10% of a CFC[4] to include their pro rata share of the CFC's GILTI in their current income. GILTI is calculated as the net CFC tested income (gross income minus certain exclusions and deductions) minus the net deemed tangible income return (10% of the shareholder's pro rata share of the adjusted tax basis of tangible depreciable property, reduced by allocable interest expense).

U.S. corporate shareholders can generally deduct up to 50% of their GILTI inclusion pursuant to section 250,[5] reducing the effective tax rate to 10.5%.[6] They can also claim an indirect foreign tax credit for 80% of the foreign taxes paid by the CFCs on GILTI. However, these benefits are generally not available to individuals[7].

For U.S. shareholders with multiple CFCs, GILTI is calculated on an aggregate basis, netting tested income and losses across all CFCs. If the net result is a loss, the GILTI inclusion is zero. Similarly, a U.S. federal consolidated return group is treated as a single taxpayer for GILTI purposes, netting tested income and losses across the group.

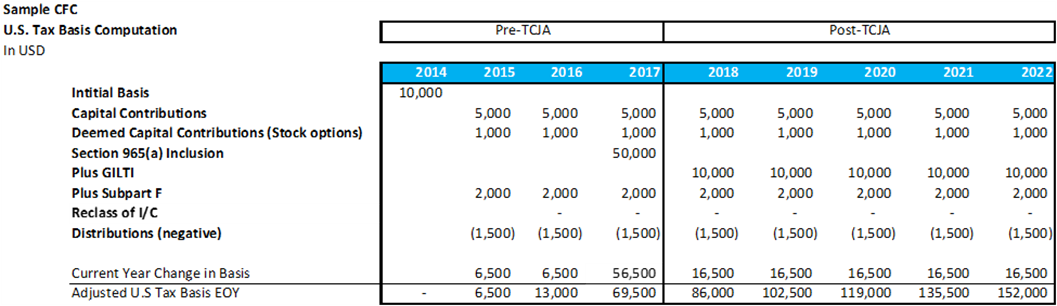

CFC stock basis adjustments

The rules for determining the tax basis in the stock of a CFC have evolved with the enactment the TCJA. Despite some differences between the pre- and post-TCJA regimes, certain factors consistently increase the tax basis under both systems, including capital contributions[8] and Subpart F income[9]. In general, distributions of previously taxed earnings and profits (“PTEP”) under the post-TCJA regime, and previously taxed income (“PTI”) under the pre-TCJA regime, decrease the tax basis in CFC stock, but not below zero.[10]

Before the TCJA, the U.S. followed a worldwide system for CFC taxation, allowing U.S. shareholders to defer U.S. taxation on CFC profits until those profits were repatriated to the U.S. This system often resulted in the long-term offshoring of profits.[11] The TCJA introduced a hybrid-territorial system, requiring U.S. shareholders to include CFC income as current income,[12] thereby eliminating the long-term offshoring allowed under the pre-TCJA regime.[13]

The TCJA also introduced the one-time section 965(a) inclusion as well as the GILTI provisions. Section 965(a) mandated a one-time inclusion in income for U.S. shareholders of CFCs, based on the accumulated post-1986 deferred foreign earnings, which increases the tax basis in the CFC stock.[14] As discussed above, the GILTI regime under section 951A requires U.S. shareholders to include their share of the CFC's GILTI in their gross income, also resulting in a basis adjustment to prevent double taxation.

Below is an example of a CFC tax basis calculation, with most amounts held constant from year to year to highlight the changes and similarities between the pre- and post-TCJA calculations. (Note that the section 965(a) inclusion occurred in the 2017 tax year).

CFCs in financial distress

Creditor Considerations

Worthless stock deduction

Section 165(g) generally provides that if a security (including a share of stock in corporation) becomes worthless during a taxable year – such loss shall be treated as a loss from the sale or exchange, on the last taxable day of the year. Section 165(b) states that the basis for determining the amount of the deduction for any loss shall be the adjusted basis provided in section 1011 for determining the loss from the sale or other disposition of property.

For example, assume a U.S. shareholder owns shares in a CFC with an adjusted basis of $100 and the CFC become wholly worthless during the year. The U.S. shareholder would thus be entitled to a $100 capital loss.

Section 165(g)(3) provides an exception to capital loss treatment by allowing a domestic corporation an ordinary loss on the disposition of an affiliated corporation. To qualify as an affiliated corporation, the U.S. corporation must directly own 80% of the vote and 80% of the value of the subsidiary.[15],[16]

In addition, section 165(g)(3) generally requires that more than 90% of the aggregate of the subsidiary’s gross receipts for all taxable years have been from sources other than royalties, rents, dividends, interest, annuities and gains from sales or exchanges of stocks and securities.

As such, if a controlled foreign corporation (CFC) becomes wholly worthless, the U.S. shareholder can claim a capital loss deduction equal to its adjusted basis in the stock of the CFC under section 165(g). However, if the requirements of section 165(g)(3) are met, they can instead claim an ordinary loss. Based on the previous example, if the requirements of section 165(g)(3) are met, the U.S. shareholder would have a $100 ordinary deduction (rather than capital loss).

As section 165(g)(3) requires direct ownership, the provision is not available if the worthless stock deduction was not taken with respect to a first-tier CFC. Alternatively, if a solvent intermediary CFC could be liquidated – then section 165(g)(3) treatment might be available. However, the transaction would also subject to the Treas. Reg. section 1.165-5(d)(2)(ii) anti-abuse rules.[17]

Bad Debt Deduction

Section 166(a)(1) allows for a deduction for any debt that becomes wholly worthless during the year. The amount deductible equals the adjusted basis of the debt.[18] Under certain circumstances, section 166(a)(2) provides for partially worthless debt deductions.

For example, assume a CFC owes its U.S. shareholder debt with an adjusted basis of $100. It is determined that the debt has become wholly worthless in 2024. As such, the U.S. shareholder can take a $100 bad debt deduction.

Debtor CFC Considerations

Cancellation of Debt Income

While the shareholder creditor may take a bad debt deduction or worthless stock deduction, the debtor generally would have correlative cancellation of debt income (“CODI”). Section 61(a)(11) provides that CODI is included in taxable income. For example, assume a corporation borrows $100 from a creditor. The corporation increases an asset (cash) and has a corresponding increase to its liabilities (note payable). If the creditor forgives $100 of the loan,[19] then the corporation has been relieved of $100 of liabilities, and thus would reflect $100 of CODI.

Since CODI is included in taxable income[20] and CFCs are treated as domestic corporations for purposes of calculating gross income under Treas. Reg. section 1.952-2(a)(1), taxable CODI is likely includable in the calculation of GILTI as section 951A(c)(2)(A) tested income. However, to the extent available,[21] the section 250 deduction could offset up to 50% of such GILTI income.

There are two important exceptions to this rule. To the extent the debtor is insolvent, section 108(a)(1)(B) provides that such CODI is excluded by the amount of insolvency immediately before the debt discharge. In the prior example, if the debtor is insolvent by $40 immediately before the debt discharge, $40 of the CODI would be excluded from taxable income (and $60 would be taxable to the debtor).[22]

Another prominent exclusion is the bankruptcy exclusion, in which CODI is excluded if the discharge occurs in a “title 11 case.”[23] The term “title 11 case” means a case under the Bankruptcy Code[24] if the taxpayer is under the jurisdiction of the court; and the discharge of indebtedness is granted by the court or pursuant to a plan approved by the court.[25] Where a debt cancellation occurs during the bankruptcy process, but not pursuant to a plan approved/granted by the court, the bankruptcy exclusion does not apply.[26] If the debt discharge occurs pursuant to a plan approved by the court, the level of insolvency of the debtor is irrelevant to the amount of the exclusion. In other words, the burden of proof is on the taxpayer to establish the amount of insolvency outside of a title 11 bankruptcy case.[27] One benefit of a title 11 bankruptcy filing is the absence of the requirement for the taxpayer to establish the amount of insolvency.

Generally, where an exclusion (i.e., bankruptcy or insolvency) applies, a tax attribute reduction is required under Section 108(b), which provides mechanical ordering rules. The mechanics of the attribute reduction resulting from excluded CODI is beyond the scope of this article; however, while not entirely clear, it appears logical that tax basis in assets of a CFC would be reduced to the extent that CODI is excluded due to insolvency or U.S. title 11 bankruptcy.[28]

Attribute reduction generally has the effect of providing the debtor with a “fresh start” – such that the CODI is excluded from taxable income (due to insolvency or bankruptcy) after the determination of tax for the year in which debt is cancelled.[29] The cost of reducing attributes is that future income and taxes would likely be increased. For a CFC, the loss of basis in assets would have the effect of reducing depreciation deductions, which would have the effect of increasing tested income and thus the GILTI inclusion to the U.S. shareholder.

Revenue Ruling 2003-125

Revenue Ruling 2003-125[30] clarifies the tax consequences when a U.S. shareholder converts a CFC to a disregarded entity. Specifically, the ruling addresses the conditions under which a shareholder can claim a worthless security deduction under section 165(g)(3), with regards to a CFC.

In Situation 2 of the ruling, P, a domestic corporation, owned all equity interests in FS, a foreign subsidiary. On July 1, 2003, P filed a valid Form 8832 to change FS's classification from a corporation to a disregarded entity. At the close of the day before the election, the fair market value of FS's assets, including intangible assets such as goodwill and going concern value, did not exceed its liabilities (meaning, FS's stock was worthless). Consequently, P did not receive any payment for its FS stock in the deemed liquidation. The deemed liquidation is an identifiable event that fixes P's loss, allowing a worthless security deduction under section 165(g)(3) for the 2003 tax year.

The ruling clarified that when a U.S. shareholder owns an insolvent CFC, changing the classification of the CFC to a disregarded entity can result in a section 165(g)(3) worthless stock deduction. Additionally, the creditors of the former CFC, may be entitled to a deduction for a wholly or partially worthless debt under section 166.

This ruling provides a clear pathway for U.S. shareholders of CFCs to recognize losses on worthless stock and claim appropriate deductions, thereby offering tax relief in situations where the CFC's liabilities exceed its assets.

Conclusion

Navigating the tax consequences for financially distressed CFCs is complex, particularly under the post-TCJA international tax rules. For CFCs in financial distress, understanding the relevant provisions such as section 165(g)(3) for worthless stock deductions and section 166 for bad debt deductions is crucial. Effective tax planning can help U.S. shareholders manage the tax implications of their investments in financially distressed CFCs.

This article was originally published in the AIRA Journal, Vol. 37, No. 4 in 2024.

- [1] All section references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (the “Code”), as amended, or to underlying regulations.

- [2] Section 961(a)

- [3] Section 961(b).

- [4] Note that section 957 requires that 50% of the vote or value of a foreign corporation is required to be owned by U.S. shareholders on any day of the taxable year of the foreign corporation to be treated as a CFC. The GILTI rules thus apply to any 10% shareholder of a foreign corporation that meets the section 957 CFC definition.

- [5] Note that the section 250 deduction is computed after net operating losses (“NOLs”). If the section 250 deduction is reduced or eliminated due to NOL deductions, the unused section 250 deduction cannot be carried forward. In other words, the section 250 deduction must be used in the year of the GILTI (and/or other inclusions) or is otherwise lost.

- [6] The deduction will be reduced for tax years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, from 50% to 37.5%. This change effectively increases the GILTI inclusion rate for domestic corporations from 10.5% to 13.125%, assuming the corporate tax rate remains at 21%.

- [7] Note that these benefits would be available to individuals and trusts that make a section 962 election.

- [8] Note that issuances of U.S. parent stock to a CFC relating to employee stock option plans are included in capital contributions.

- [9] Defined in section 951(a) and discussed below.

- [10] Section 959 provides that such distributions are excluded from taxable income of the U.S. recipient. This is intended to prevent double taxation in most cases. The U.S. Treasury is in the process of drafting regulations that will attempt prevent double taxation in certain cases where double taxation remains.

- [11] The U.S. enacted a tax holiday in 2004 that reduced the tax rate on repatriated cash from 35% to 5.25%. This resulted in $362 billion of cash being repatriated in that year. Martin A. Sullivan, Corporate Tax Reform: Taxing Profits in the 21st Century, p. 83, ISBN 143023928X.

- [12] U.S. shareholders may be eligible for a 100% dividends-received deduction, subject to certain limitations. Note that high-taxed GILTI is excluded from income.

- [13] Note the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (“OECD”) has proposed a “global minimum tax” of 15% for large corporations, with an effective date of 2024. The global minimum tax is based on a two-pillar approach. Pillar One relates to where taxes will be paid. Pillar Two relates to how the global minimum taxes will be paid.

- [14] While the 965(a) inclusion could have been paid in installments in tax years beginning in 2017, the increase to basis would have occurred in 2017, regardless of when the payments were actually made.

- [15] As defined in section 1504(a)(2).

- [16] Note that Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.165-5(d)(2)(ii) provides an anti-abuse rule that provides that: “None of the stock of such corporation was acquired by the taxpayer solely for the purpose of converting a capital loss sustained by reason of the worthlessness of any such stock into an ordinary loss under section 165(g)(3).”

- [17] Id.

- [18] Treas. Reg. section 1.166-1.

- [19] The creditor would presumably take a bad debt deduction.

- [20] In a 1997 Private Letter Ruling, the IRS stated that a CFC’s CODI would not ordinarily be considered Subpart F income as CODI is specifically enumerated as its own type of income under Section 61(a)(11): LTR 9729011 (Apr. 11, 1997).

- [21] As discussed above, the section 250 deduction is calculated after the NOL deduction.

- [22] Note that insolvency is a factual issue that may be challenged by the IRS.

- [23] Section 108(a)(1)(A).

- [24] Title 11 U.S.C. Note that a Chapter 7 (liquidating) or Chapter 11 (reorganizing bankruptcy) are two examples of title 11 bankruptcies.

- [25] Section 108(d)(2).

- [26] For example, if during the bankruptcy proceedings, the debtor and creditor independently agree to a modification of the debt, or the debtor buys back its debt for stock at a discount, all without the court’s approval.

- [27] Note that a Chapter 7 (liquidating) or Chapter 11 (reorganizing bankruptcy) are two examples of title 11 bankruptcies.

- [28] Corporations are eligible to file a U.S. bankruptcy case if they have some nexus to the U.S., per Bankruptcy Code section 109(a). Foreign corporations commonly file U.S. Bankruptcy cases when there are U.S. creditors.

- [29] See section 108(b)(4). For example, if tax basis in the assets of a CFC was reduced in the 2024 tax year, depreciation relating to such assets would be available in the determination of tax for 2024. However, to the extent that basis in such assets were reduced in the 2024 tax year, such basis would not be available to be depreciated beginning the first day of the 2025 tax year.

- [30] Rev. Rul. 2003-125, 2003-2 C.B. 1243.

Let’s Talk!

You can call us at +1 213.873.1700, email us at solutions@vasquezcpa.com or fill out the form below and we’ll contact you to discuss your specific situation.

Required fields are marked with an asterisk (*)

This article was written by Michael Barton, Nate Meyers and originally appeared on 2025-01-14. Reprinted with permission from RSM US LLP.

© 2024 RSM US LLP. All rights reserved. https://rsmus.com/insights/tax-alerts/2025/maximizing-insolvent-cfc-value.html

RSM US LLP is a limited liability partnership and the U.S. member firm of RSM International, a global network of independent assurance, tax and consulting firms. The member firms of RSM International collaborate to provide services to global clients, but are separate and distinct legal entities that cannot obligate each other. Each member firm is responsible only for its own acts and omissions, and not those of any other party. Visit rsmus.com/about for more information regarding RSM US LLP and RSM International.

The information contained herein is general in nature and based on authorities that are subject to change. RSM US LLP guarantees neither the accuracy nor completeness of any information and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for results obtained by others as a result of reliance upon such information. RSM US LLP assumes no obligation to inform the reader of any changes in tax laws or other factors that could affect information contained herein. This publication does not, and is not intended to, provide legal, tax or accounting advice, and readers should consult their tax advisors concerning the application of tax laws to their particular situations. This analysis is not tax advice and is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for purposes of avoiding tax penalties that may be imposed on any taxpayer.

Vasquez + Company LLP has over 50 years of experience in performing audit, tax, accounting, and consulting services for all types of nonprofit organizations, governmental entities, and private companies. We are the largest minority-controlled accounting firm in the United States and the only one to have global operations and certified as MBE with the Supplier Clearinghouse for the Utility Supplier Diversity Program of the California Public Utilities Commission.

For more information on how Vasquez can assist you, please email solutions@vasquezcpa.com or call +1.213.873.1700.

Subscribe to receive important updates from our Insights and Resources.